16 AUG 07

How has your first book changed your life?

87. Joshua Kryah

How did you find out that your manuscript won the 2005 Nightboat Poetry Prize?

A phone call during a poetry reading. I was at UNLV listening to Maxine Chernoff, when the Nightboat editors left a voice message. In the message, Kazim and Jennifer, my editors, told me that they had "good news." I was so excited that I didn't call them back. Instead, I walked around campus a few times, savoring the news without confirming it or telling anyone. There was something about the space between knowing and not knowing that I wanted to hold onto for a while.

I had been working on the manuscript for four or five years. Now that it was about to happen, I wanted to sustain a sense of disbelief or naïve ignorance, to speculate otherwise, to almost turn away from it. But the prospect of having Glean published created the most delicate and evanescent of moments. I knew that there was no longer the possibility of writing in anonymity. That kind of commitment was terrifying. It scared the hell out of me.

It still does.

How often had you sent it out previously?

Consistently for a little over two years. I sent to a lot of contests and spent a lot of money. I understood that contests were the most likely avenue for publication, but I wasn't happy about it. I don't know that anyone is. The charitable urge to support presses through entrance fees for contests is, I think, immodest. None of us really wants to receive a copy of the winning book as much as we do our own.

I understand, however, the current state of poetry publication and why such fees are necessary. I also understand how these fees result in the publication of books like Glean. But every time I sent out my manuscript with a check, I felt uncomfortable, dirty.

And contests are dirty. There are always losers. And a lot of them, including myself, don't take losing well. I became pretty pessimistic during those two years. It was tough to remain humble, to feel supportive of others' successes. I tried. But it's difficult when we're all competing for the same things. I hope to be more humble now that Glean is out. I have no reason not to.

What do you remember about the day when you saw your finished book for the first time?

My wife, Amber, designed Glean, so I was intimately involved with the physical production of the book from the very beginning. This had always been a fantasy of mine, to make the book into a collaborative effort, particularly with Amber's background in book design.

We worked on the design on and off for about nine months. Actually, Amber experimented with type treatments while I sighed and fretted and generally got in the way. And this was during her pregnancy with our first child. Together, we chose the type for the poems and titles, the margin spacing, the line leading.

What I'm really happy with is the inclusion of my birth year on the copyright page. Not many books do birth years anymore. I'm always intrigued to know when someone was born in relation to their publications, especially if it's a first book. I want people to know I was born in 1974.

When the printed book finally arrived, we were ecstatic. It's the complete package, beautifully constructed and rendered. The size is unconventional and the spacing is more open, more ventilated than most other books. It gives the poems room to move around, to interact with the page, to be themselves. It's gorgeous. Whenever anyone tells me how much they like Glean, they usually say, "It's beautiful! I haven't read it yet, but it's just a beautiful book!" It really is.

Were you involved in designing the cover?

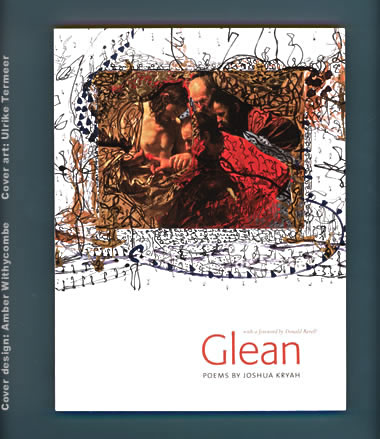

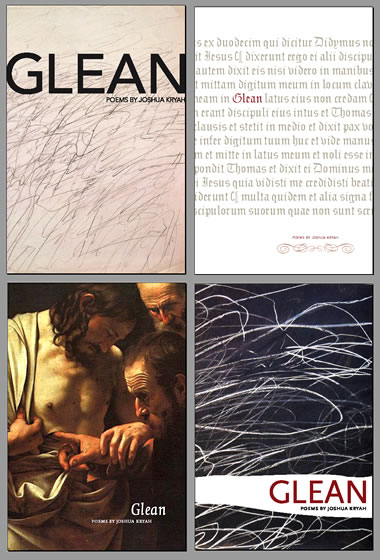

Very. Originally, we had planned to use a drawing by Cy Twombly, something very modern, very graphic. However, there were certain restrictions on the artwork that we were unhappy about. Fortunately, one of the editors at Nightboat has an aunt in Germany, Ulrike Termeer, who is a fantastic artist and agreed to create a piece specifically for the book.

Once we saw a catalogue of Ulrike's work, we were immediately intrigued. One series in particular caught our attention. "Proust und die Maler" re-works or defaces paintings by old masters like Bruegel, Poussin, Ingres, Vermeer, and Corot. It's a very post-modern approach to canonical representations of art. And this worked perfectly with another idea I'd had for the cover.

I'd previously considered Caravaggio's depiction of Doubting Thomas for the cover, but thought it was too austere, too romantic. We've all seen them, books of poetry with classical paintings on the cover, testifying to the gravity of the poems inside. I did and didn't want this.

So when I saw Ulrike's "Proust und die Maler" series, I knew I could have both the preciousness of the original and the edginess of its reinterpretation.

Ulrike was extremely receptive and accommodating. I imagine it's rare to commission an artwork from an established artist these days, particularly by the likes of a no-name poet with a print run of a thousand books. There wasn't much in it for her, but she took to the project with such zeal and consideration that the resulting painting defied my expectations. It's exuberant, feverish, worked up. Really, it's just wonderful. So much so that we reprinted the entire painting inside the book to give readers the full effect, though in black and white.

And the glob of red placed on Christ's wound is great. It covers up the gratuitousness of Caravaggio's original slit, while at the same time highlighting its significance. I love it, that red. The way it echoes the red of Thomas' coat, how it picks up on the red that abounds in the poems.

I should mention that the impact of Ulrike's artwork wouldn't have been felt in the same way if it hadn't been for Amber's design. She came up with the crisp, white background, the cropping of the artwork and title--everything that makes the painting work as a cover.

Before the day you first saw your book, did you imagine your life would change with its arrival?

No. I mean, yes. Both. I knew the book would lend a legitimacy to my writing that hadn't existed before. I knew that having the tangible proof of my labor would better explain to people my aesthetic. I knew this would be particularly helpful for my family and friends, who had often struggled to understand my writing. If anything, I knew the book would act as justification for all the time I'd spent in graduate school or garretted in my office, scribbling.

I knew the publication of Glean would also substantiate my ambitions as a poet, and I also knew that it would lend me currency in the current literary environment. How much or how little I wasn't sure, but that didn't seem to matter. I knew if I wanted to make a life in poetry, the book would have to come first. And so it has. And that seemed the biggest hurdle. I think the rest becomes easier. At least I hope so.

Has your life been different since?

Yes, but not necessarily because of the book. At about the same time that Glean was published, my wife and I had our daughter, Eavan. I was also finishing my Ph.D. studies. So there was a lot happening in my life. And in a way, that was helpful. It allowed me some perspective on the entire process, particularly the book's reception. I had initially hoped to do everything I could to get attention for Glean, but being exhausted from the demands of a new family and my Ph.D. exams, I was happy to let things take their own course. And so they have and continue to do so.

Were there things you thought would happen that didn't? Surprises?

Not really. The market is flooded these days with new books of poetry, new poetry presses, new hot young poets--there's too much to keep up with. I'm just happy to have had my day.

What have you been doing to promote Glean and how do you feel about those experiences?

I've put together a few readings, as much as time and money permit. It's difficult to travel now that I'm a father. I feel guilty about leaving home for long periods of time.

The readings I have done, however, have been wonderful. I'm still getting used to the format. It's getting easier, more comfortable. At first it almost seemed like a chore. Or I made it seem like a chore in order to calm my nerves. Once I got used to standing in front of an audience I began to work on my projection, pacing, rocking back and forth on my heels. I enjoy it. I dread it, but I enjoy it.

What advice do you wish someone had given you before your book came out? What was the best advice you got?

Send it out. Nightboat gave me close to seven months to revise the manuscript. It was during this time that the manuscript really became what it is. In fact, some of the best poems were written during this time, when I didn't have to worry about contests and publication. Not that the manuscript was paltry before then, but it wasn't yet fully realized. This shouldn't necessarily deter anyone from submitting their manuscript. You'll have time to revise it later, without the pressure, without the hassle. You'll finally have a moment of peace away from the insistent din of contest deadlines.

What advice would you give to someone about to have a first book published?

Send it out. Paul Hoover suggested I send copies of the book to every poet I admired. And I have. Some have responded, some haven't. It really doesn't matter. The opportunity to share my work with these writers is what counts. I'm grateful I've had the chance to do it.

What influence has the book's publication had on your subsequent writing?

More than anything, it's allowed me to relax, to find some of the humility I spoke of earlier. Obviously, I no longer feel the overwhelming need to get a book published. I'm very content with taking my time with new poems, allowing Glean to make its way into readings, workshops, reviews. I have no desire to immediately publish another book, either, as it would only take attention away from Glean.

I'm also still trying to figure out where this book came from. It kind of took me by surprise. I feel as though I'm not done writing it. I've been slowly, in subtle ways, revising Glean. I often comb through it, changing a few things, adding notes, including new poems. It still feels very alive, unfinished.

How do you feel about the critical response so far? Has it had any effect on your writing?

At this point, not much. The book has only been out for six months, so there really hasn't been much of a response. And who knows if there will be? The reviews I've seen have been positive, but more importantly, smart. I find that incredibly encouraging. Particularly because it validates intelligence in poetry. It's gratifying to know that some readers recognize rigor as an integral part of both writing and reading poems.

What's been most surprising about the book's publication is the response I've received from other poets. Carl Phillips, Eric Pankey, Reginald Shepherd, and a few others have sent me some very kind words. Being welcomed by poets I admire is terribly flattering.

Do you want your life to change?

No. I only hope to gain a greater appreciation of and submission to what my life already is.

Is there something you're doing now that you think will bring about a change that you seek?

Writing. And reading.

Do you believe that poetry can create change in the world?

I should let someone else answer that. How about Celan? "Poetry, ladies and gentlemen: what an eternalization of nothing but mortality, and in vain."

:

2 poems from Glean by Joshua Kryah:

Called Back, Called Back

Acquit me, make me

purblind, unbloomed, a thing that,

when aroused,

remains dormant, unused, none

among many. As the bulb that persists within its sullen,

despondent mood, alive, but no more, no better

than some kind of senseless meat.

I turn away but wherever I turn I encounter

the same soft refrain--

I did not call you, lie back down.

I did not call, lie back, lie down.

There is death and then

there is sleep, or I no longer know who's

calling or

what I've heard or what I'll say. As, when roused once more

by your voice-light, its endless drag and weight,

I move

as a tuber on the verge of swelling, the called-forth,

fruited body, caught between monad and many,

between almost and already.

Numen

Provocation, voicelet,

what moves in me awaits

credulity, a torn sheet in which to wrap its weight.

Solicitous attendant, o pilgrim, from the charnel

house you must transpire,

a shudder, a complaint.

~

What stirs is not ancestry.

Nor the inception of any one blood.

But the insistence to wake,

to bear witness, comes

as a stranger, from no one's mouth, no

other arrangement.

~

Your tongue, speech-pocked, unnerved, a whip

circling overhead.

My body forced to it, listening and

listening.

The imagined crack, its hiss, or what

it might have said:

let those believe who may.

A summons

(let those believe) that gathers

to itself a certainty, (let those believe

who may) the more

it leaves one behind.

~

And belief now an unrest, growing

singly in search of a pair,

the absence of some other, your voice calling

out to me--

skeptic, refuser, Thomas' head

as it continues to shake.

(know this)

I would not be here without you.

. . .

next interview: Alex Lemon

. . .