10 DEC 06

How has your first book changed your life?

42. Oliver de la Paz

What do you remember about the day when you saw your finished book for the first time?

I was teaching at Gettysburg College as the Emerging Writer Lecturer at the time. I had just finished teaching my creative writing class, so I was a bit tired...ready to go home. When I went to the department office to check for my mail, there was a flat cardboard book mailer in my mail slot from Southern Illinois University Press. I opened it up as fast as I could and I remember seeing the gleam of the office lights reflecting off the glossy black cover. Fred Leebron, and Kathryn Rhett were my mentors during that year at Gettysburg, and I showed them my book. They congratulated me and gave me some book promotion advice (don't give away your copies, use those for reviews, press kits, etc.) When I was done with my parade through the English department, I went home and called my parents.

I didn't proofread or double-check any of the poems. I didn't look for any editing issues. "Finished" is a good word to describe how I felt about the pieces in the book before I received my first author copy. Many of those poems were written from 1995 to 2000, so I was tired of looking at the poems in manuscript form. I'm funny about publication in that respect. I send stuff out in order to stop my brain's editorial impulses. While I was in the process of sending the manuscript out, I was revising the poems and the poem order constantly. The phone call from Jon Tribble, the editor for the Crab Orchard Poetry Series, came while I was revising and printing out the manuscript for other book contests. I think I was on draft number eight when he called. My laser printer was running out of toner and spitting out the last of some manuscript pages I had revised.

Before that day, did you imagine your life would change with its arrival?

When I was in my first year of graduate school, there was a glamour I had assigned to being a poet with a book, but that was quickly deflated when I went to my first AWP conference in Portland, OR. There were so many poets. There were so many poets with one book. It was all pretty intimidating. All of a sudden, the writing world seemed a lot bigger, less intimate.

I did have the benefit of having a supportive group of friends in the MFA program at Arizona State University, and some wonderful mentors. Together, my friends and I would go to Gold Bar, a coffee house between Mesa and Tempe, and we'd write, read, and talk for hours. Anyway, before the arrival of the book, I was nervous about my future. Being of immigrant stock, my family had a strong investment in my success as the one and only son. As an undergrad, I was a double major (Biology/English). I thought for sure I'd be a doctor and fulfill my filial duty. Even today my father suggests that I should further my education either in law school or in a PhD program (my mother keeps him in check. He usually talks to hear himself talk). So...there was a bit of pressure to succeed. Meanwhile, the happy fantasy world of graduate school was ending.

I had the belief that a book would be what got me hired at an institution of good repute. I'm embarrassed by that shortness of vision now, even though it did help me land my current job. I was more concerned about being gainfully employed and I didn't want to fit the "starving artist" stereotype. I felt that having a book would help me land an academic job--a book was "the golden ticket." Lord knows I wanted a gig like the ones my writing professors had.

When the book got picked up, I was a lecturer at ASU, teaching eight composition classes per year. Each class had about 25 students, so I had a lot of paper work in the evenings. (The ideal job for many writers who aspire to teach in MFA programs and PhD programs is a 2/2 load, or two classes per semester.) It was actually a pleasant time. I'd quickly grade homework at home and dive back into my reading, writing, and revising. All the while, I was figuring out who I was as an artist and as a teacher. And I didn't have the same fear of failure that I had as a student. I had some distance from the "professional development" mantra that was buzzing around the other graduate students. It was a very strange turn. I guess it came about because I had ended my schooling, realized the world wouldn't end, and had some badly needed perspective. The call from Jon Tribble came when I was a lot healthier in spirit.

How has your life been different since?

Well, for starters, I'm no longer teaching a four/four composition load. I'm gainfully employed, married, I have to pay a home mortgage... All those fairly conventional things that are supposed to happen as you get older happened to me (no kids, just a whiny German Shorthair Pointer).

I now get occasional e-mails from Filipino/a students, telling me about how much my work means to them. I also get e-mails from students asking me about certain themes in the book (I'm assuming as part of a homework assignment). There are also students and professors who ask their schools to bring me in for speaking engagements, which is always nice, especially since I usually get a small honorarium for speaking.

I'm also involved with Kundiman, a not-for-profit organization committed to the discovery and cultivation of emerging Asian-American poets. The wonderful poets Joseph Legaspi and Sarah Gambito are the visionaries for this organization, and we have an annual summer retreat on the campus of UVA. The organization puts me in contact with a number of fabulous Asian-American writers who sometimes ask for advice, feedback, or general support.

Finally, my writing has changed dramatically from the days before the book. I'm a more deliberate writer. I write in sequences and in series now, whereas before I could write disparate poems--pieces that were independent of a sustained narrative or from a thematic concern. Now I have to write pieces that interconnect/interrelate. Part of that has to do with my interest in the overall construction of a book that was informed by my construction of Names Above Houses. Also, my writing time is more regimented. I have designated writing days now, because of my employment at a university. Summers are my buzz times when I'm not encumbered by student papers or reading course materials.

Needless to say, all that change slowed my writing down a bit. My second book, Furious Lullaby, took me almost seven years to finish. Hell, I'm still fiddling with order now, even though SIU wants me to mail them my final formatting. It should be out in the Fall of 2007.

Were you involved in designing the cover?

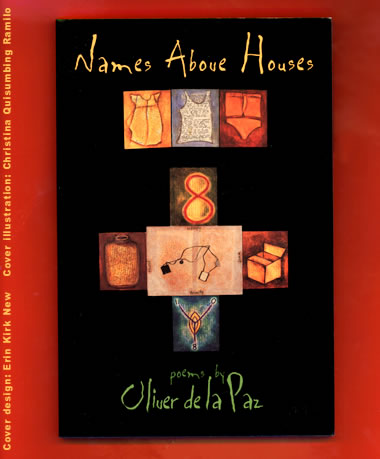

I wanted a Filipino/a artist to design the cover. That's the one thing I absolutely wanted because Names Above Houses is about a Filipino community. I e-mailed Filipino/a writers like Bino Realuyo, Eileen Tabios, and Nick Carbo for names of artists. I also surfed the web for interesting art galleries that showcase Filipino/a artists.

The one compliment I kept hearing from everybody was that the cover was stunning. Southern Illinois University Press did an amazing job with the cover, even though at the beginning we were having image quality issues. It's an installation piece done by Christina Quisumbing Ramilo entitled "Pasyon." She took these letters that were between she and her mother, painted and laminated them onto small blocks, and arranged the blocks as you see on the cover. Because it's a three-dimensional image, it was difficult to get the blocks "just right." Anyway, I was remembering some of the problems we had during the early stages of cover design and I was very pleased with the end result.

Were there things you thought would happen that didn't? Surprises?

I'm always surprised by people who assume the character in the book is me. Names Above Houses is pretty fabulist--it's a series of fables/parables. The kid has wings. At one reading a student asked, "When you flew off the roof, what was going through your mind?" I didn't know what to tell her. What's even more surprising is that it happens frequently. Now granted, there are some aspects of the character that are distinctly me (his obsessive compulsive tendencies, his introspection), but overall the events of the book are not events of my life.

What have you been doing to promote the book and what are those experiences like for you?

I received a nice box filled with twenty-five copies of my book. Of those twenty-five copies, I kept only a few copies to give to my parents and my mentors. The rest of the copies I shipped off in press packets to reading venues, journals, etc. SIU flew me out to give a reading in Carbondale, IL. I then got a few readings the first few months the book was out. The following year I had a lot more opportunities to read. At the time I was living in Utica, NY (my Gettysburg College lectureship ran out), and I was only a four-hour train ride away from New York City. So I read at venues like the Asian American Writers' Workshop, the Ear Inn, and other places. ASU invited me to come back a couple of times for their Desert Nights, Rising Stars conference--they've supported my post MFA years.

One of my mentors told me that most books gain momentum two years after they're released, and the results of my press packets bear that out. Most of my promotional readings for Names Above Houses came in 2001-2002. I noticed it started getting adopted for Asian American literature classes and creative writing classes around 2002-2003, so those who were readers the year it first came out became my chief book promoters.

I also do a lot of community teaching, which I enjoy. I've conducted workshops at the YMCA, the AAWW, and at other non-profit gigs. This year I'll be running a workshop to benefit Doctors Without Borders. Hopefully I've turned into a resource for the writing community, particularly through my work with Kundiman and in the classroom. It's what being a poet-citizen's all about.

What was the best advice you got?

Did I mention that poet-citizen thing? Alberto Ríos, one of my mentors at ASU, was fond of that term. I think it's a good way to think of this thing we do as we give readings, teach workshops, and write reviews. I strive to be generous with my time in the community, in the classroom, at reading venues, and "off camera." When a poet's first book comes out, I buy that book and try to bring them to my school for readings (I try to buy as many first-books as I can afford). Finally, I try to be gracious in all things, whether that be teaching workshops, reading other people's manuscripts, or performing at venues. I write thank you notes/e-mails after readings and after someone has been generous enough to read and accept my poems for journals, contests, etc.

What influence has the book's publication had on your subsequent writing?

Right after I finished my time at ASU, I was working on a "darker" series of poems. I was determined to write something completely different from Names Above Houses. Unlike the prose/character-driven poems of Names Above Houses, the new stuff was lineated, short, and lyrical. I wrote a series of about eight of those poems before I had to stop due to a cross-country move, a new job, and other life-changes. A part of me felt that I had forgotten how to write a line-break after the first book, so those small lyrical pieces were experiments for me. Later, I started writing my Rube-Goldberg poems (as I like to call them) as a function of being stuck on these small lyrics. The small pieces were too dense, too sound-driven. I didn't know what was going on in those poems, didn't have any perspective for the work.

I wrote nothing for a few months. Then I decided to get back into writing by giving myself prompts. I wrote a series of Aubades that started as these Rube-Goldberg exercises: write a poem with an animal, a passage from the bible, the color teal, a scent that speaks. Write a poem with a necklace, a phrase from a Bee Gees song, the Aurora Borealis, and a plant indigenous to Minnesota. The one thing that helped me unify these disparate elements was narrative. I guess you return to the things you do best. Ultimately those longer puzzle-like pieces unified what I was doing in the smaller lyrics and it became Furious Lullaby. It's so very different from Names Above Houses, but truer to what I was doing before my MFA program.

How do you feel about the critical response and has it had any effect on your writing?

I've received a lot of critical response from professors who teach Asian American literature classes. The response has been positive and I've had students and professors alike ask if there's a sequel in the works. For a time there was a sequel in my brain. I had even thoughts of a trilogy of books all centered around this Filipino community, but I don't think my idea of revisiting those characters was a reaction to the critical feedback. I just liked those characters and I wanted to know what was going on in their lives.

While it's cool to have this feedback on the work, I really don't listen to what's being said. I mean, I could write another Names Above Houses, but I'm not that poet anymore.

Do you want your life to change?

On TLC, there was this special about blue-collar workers who won the Mega Bucks lottery. I'd like to be one of those folks, paying off my home mortgage, my car, my other debts. However, there's always a moment in those shows where viewers see the aftermath of the sudden fame and fortune--new millionaires over-spending and declaring bankruptcy, family members fighting family members, tragedy everywhere. I'm happy with my life. I've got a job I enjoy. I'm married to a wonderful woman. We sing '80s songs to each other and watch a ton of homeowner porn on HGTV and Discover. We make walking trails on our property and run our hyperactive dog in the rain. We laugh a lot. I'm sure our lives will change, and that's okay.

Do you believe that poetry can create change in the world?

You have to start small, of course, but yes. So much of my worldview is wrapped up in my teacherly subject position. (A subject position is basically the position someone takes based on life experiences, race, culture, gender, religion, etc. I've been teaching for almost fourteen years. The way I view poetry, politics, the world, is colored by my attempts at solving problems and finding ways to explain how I've solved my problem to students so that they can share the experience.) One of the things I try to emphasize is that reading poems is a dialogical act. Reading is compassion. It's a moment when a person sits down quietly and listens to someone thinking or speaking. A poem is a moment of private dialogue, a stoppage of time, a careful listening. (If only more people in the world stopped what they were doing and read poetry!) By some measure, I try to create a small world change through my teaching and in my poems.

:

2 poems from Names Above Houses by Oliver de la Paz:

The Box of Stars

When Fidelito should be sleeping, he instead pulls from under his bed a flashlight and a blue box holding cards with names of constellations. They glitter when held to light, pinholes poked through cardboard to match the sky's geography. Fidelito, mouth opened wide, holds the butt of the flashlight between his teeth. Over the narrow beam, he projects Orion on the ceiling.

Above, the dust motes spiral in the light: Sirius, Arcturus, Capella. He points at a bright blossom in the mica and tries to say its name. The glow of streetlamps bleed into the galaxy of his room. And on the pavement after rain, the headlights of a lone car fade in the bright glint of quartz trapped in asphalt. The driver, looking out his side window, sees three stars from Orion's belt lifting the boy's ceiling to the sky.

For Hours, Fidelito Hangs from the Topmost Branch

Before Letting Go

Because, after rain, it smells like green tea his mother brews on slow mornings, because he likes the view of the world upside down from this height, he hooks his legs around the topmost branch of the world's sixth-largest Douglas fir. Fidelito has a mission. There is a certain grace with trees, he thinks, and hanging from one for a long time will show him how little he needs his legs, whether his dreams are different, whether he is closer, the way mountains or skyscrapers or even Douglas firs scratch the back of the sky.

If Fidelito is part of the order of back-scratchers he will know simply by hanging around until slowly his blood, in an act of defiance, rouses itself from his feet and leaves in procession down the arteries of his knees, marching, red ants renewing their contract with gravity, and dizzy, Fidelito lets go.

. . .

next interview: Rachel Levitsky

. . .